- LittleLaw

- Posts

- 🍻 The $1 billion BrewDog deal that left everyone empty-handed

🍻 The $1 billion BrewDog deal that left everyone empty-handed

Table of Contents

If you take just one thing from this email...

BrewDog (the craft beer brand) took private equity money with strings attached — TSG was promised an 18% return before anyone else got paid.

But now the company isn’t worth enough to pay that bill, which means regular shareholders (like fans and employees) could walk away with nothing.

It’s a clear warning: how you structure a deal matters just as much as how big it looks.

EDITOR’S RAMBLE 🗣

Last week I made a video explaining how different law firm names are pronounced.

In it I show you how to say:

Dechert (“de-kert”)

Fried Frank (“freed frank”)

Perkins Coie (“perkins coo-ee”)

I want to do more of these — so if there are any law firm names you never quite know how to pronounce, reply to this email to tell me!

– Idin

FEATURED REPORT 📰

🍻 The $1 billion BrewDog deal that left everyone empty-handed

What’s going on here?

James Watt, co-founder of the craft beer brand BrewDog, is locked in a power struggle with his own investors.

The tension is that a group of shareholders is pushing for a sale — but they don’t have the votes to make it happen. Meanwhile, others (including his own employees) worry a sale now would leave them with nothing.

What’s BrewDog’s story?

BrewDog was founded in 2007 by two school friends — James Watt and Martin Dickie — with a £20,000 bank loan and a mission to shake up the UK beer market.

Credit: Scotsman

They opened their first bar in Aberdeen in 2009, but avoided traditional investors. Instead, they turned to the public.

They ran a crowdfunding campaign, Equity for Punks, let anyone buy ordinary shares in the company. The first round raised £750,000 from over 1,300 people.

It worked, and over time, BrewDog raised £74 million from more than 100,000 retail investors around the world — all in exchange for ordinary shares (remember that, it matters later).

🤔 What are the different types of shares?

Ordinary shares are the standard type of share in private companies. If you own one, you usually get a vote and a share of the profits when the company does well or is sold.

But companies don’t have to treat all shareholders the same. They can create different types of shares with different rights (depending on what works best for them).

For example, one person’s shares might give them double the votes.

Another person’s shares might get paid first if the company is sold — often called preference shares (we’ll see these again later).

But things changed in 2017.

BrewDog raised money from a US private equity firm called TSG Consumer Partners.

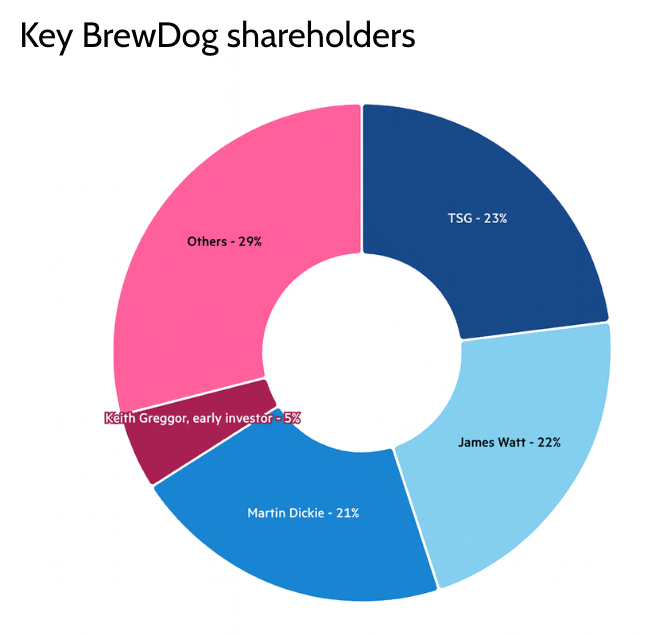

They sold TSG a 23% stake for £213 million, valuing BrewDog at around $1 billion (this number is important too). In that deal, TSG was advised by Ropes & Gray. BrewDog was advised by DLA Piper.

To make the deal work, BrewDog had to change its share structure.

How were BrewDog’s shares structured?

Before 2017, BrewDog only had ordinary shares.

These were split into two classes:

Class A ordinary shares: mostly held by founders and employees. They could be transferred freely.

Class B ordinary shares: mostly held by crowdfunding investors. These came with restrictions and could only be sold on specific platforms or back to the company.

Both share types had the same voting rights and dividend entitlements (right to a share of the profits).

But when TSG invested in 2017, BrewDog created a new class: preference shares.

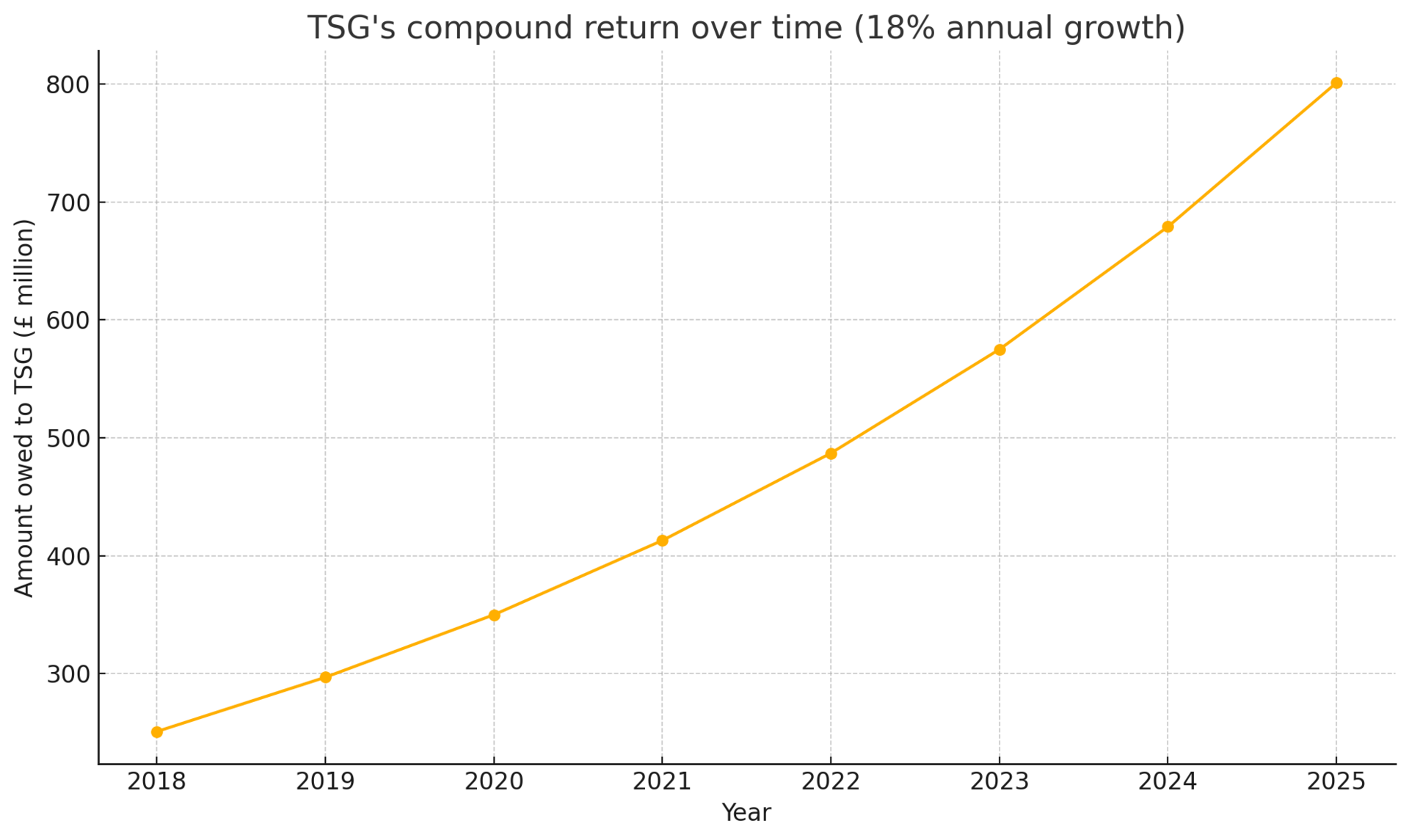

TSG was promised an 18% compound return on its investment (which means the amount they’re owed grows by 18% each year, with each year building on the last). That return only kicks in on an “exit” — like a sale, IPO, or winding up. It isn’t paid out annually. Instead, the amount owed grows over time.

Why is this a problem?

The short answer is that BrewDog probably isn’t worth enough to pay TSG what it’s owed — let alone give anything to other shareholders.

TSG’s preference shares entitle it to an 18% compound return on its £213 million investment. That return has snowballed over time. By 2024, it had grown to around £801 million.

But BrewDog’s performance hasn’t kept up.

BrewDog’s 2024 revenue was around £357 million. A buyer might value the company at 1.5 to 2 times revenue, which would put the business value somewhere between £420 million and £560 million.

But BrewDog also has £239 million of net debt — so the actual money left for shareholders after a sale would be much lower.

It’s certainly not enough to cover TSG’s payout (currently £801 million). Which means other shareholders — like the early crowdfunders — would get nothing in a sale.

That also includes some of BrewDog’s staff. Back in 2022, after James Watt was accused of creating a toxic workplace culture, he pledged to give 20% of his shares to a scheme that would benefit employees. The idea was that a portion of any future sale would be shared with them.

But if BrewDog sells now — with all the money going to TSG — those shares might be worthless.

If it hurts shareholders, why did BrewDog take TSG’s money?

At the time, the deal made sense.

TSG had a strong track record in growing consumer brands like Pop Chips and e.l.f. Its investment was meant to fuel BrewDog’s global expansion — new bars, more breweries, and growth in markets like the US, Australia, and Asia.

But it wasn’t just about business growth.

The deal also gave the founders a big payout.

Before the investment, James Watt and Martin Dickie owned 35% and 30% of BrewDog, respectively. As part of the deal, they sold a portion of their shares to TSG — pocketing £100 million between them. This kind of transaction (where existing shareholders sell their shares to a new investor) is called a secondary sale.

When a company raises money, there are two ways shares can be sold:

→ In a primary sale, the company issues newly created shares and gets the money to grow the business.

→ In a secondary sale, existing shareholders (like founders) sell their shares to a new investor. The company doesn’t get that money — the founders do.

In BrewDog’s case, part of the TSG deal was a secondary sale. It made the founders rich, but it didn’t bring extra money into the business itself.

Can’t TSG just force a sale to get its money back?

No — not on its own.

TSG owns 23% of BrewDog, meaning it holds 23% of the voting power. That’s because the company’s rules say that each share gets one vote.

To sell the company, TSG would need backing from other major shareholders (like the founders) or from lots of smaller shareholders — like those who joined through crowdfunding.

But here’s the problem: if BrewDog is sold at its current value, those smaller shareholders won’t get anything. So, they probably won’t be voting for a deal that leaves them empty-handed.

How could the deadlock be broken?

Right now, BrewDog is stuck.

TSG wants a sale, but doesn’t have the voting power. And other shareholders won’t support a deal that leaves them with nothing.

So, what are the options?

💰 1. Buy out TSG: BrewDog could offer to buy TSG’s preference shares. But TSG would likely want at least their original £213 million back — plus some of the 18% return they were promised. BrewDog probably doesn’t have the cash to do this.

🔄 2. Restructure the deal: TSG could agree to change the terms of its preference shares. For example, they might swap them for ordinary shares or agree to a lower return. That would make a sale more attractive to everyone else — but it also means TSG gives up part of what they were promised.

📈 3. Go public: BrewDog could launch an IPO. That would trigger TSG’s preference rights (since it’s an “exit“ event) — but instead of getting paid in cash, their shares would convert into a larger number of ordinary shares in the listed company. In a public company, all shareholders typically hold ordinary shares — so the preference structure falls away. This gives TSG a potential benefit if the public market values BrewDog highly.

Then the smaller shareholders — like the crowdfunders — might be offered a cash exit before the IPO. That’s common in listings with lots of smaller, individual shareholders. But the price offered would likely be low, especially given TSG’s position.

This option might be the most realistic. If TSG and the founders agree to it, they likely have enough combined votes to push it through.

How can you use this in your applications?

Here are three lessons from this BrewDog story that can help you show deeper commercial awareness in case studies, interviews, and written answers.

Insight | Explanation | When to use it |

|---|---|---|

Voting rights matter just as much as economic rights | TSG was promised an 18% return — but because they didn’t get extra voting rights, they can’t force a sale. | If you're advising a client on buying a stake in a company, ask what voting rights come with the shares. Will your client be able to pass or block key decisions? For example: an ordinary resolution (like approving dividends or appointing directors) needs over 50% of votes. A special resolution (like changing the company’s constitution or approving a sale) needs 75% or more. |

Timing can affect shareholder returns | TSG’s return is compounding — the longer the company waits to exit, the more TSG is owed. That eats into what other shareholders receive. | If you're asked about the timing of a sale or IPO, consider whether any investors have preference shares with time-based returns. Even raising the issue shows you're thinking commercially. |

A big valuation doesn’t mean everyone wins | BrewDog claimed a $1 billion valuation when TSG invested. But because TSG gets paid first — and is owed £801 million — smaller shareholders might get nothing in a sale. | If you're asked how a company should raise funds or structure a deal, go beyond the headline valuation. Ask who benefits if the company is sold. Preference shares can mean ordinary shareholders are left with little or nothing. |

In a case study, these sorts of insights show you're thinking like a commercial lawyer.

You’re not just following the story — you’re spotting the risks, incentives, and consequences behind the business choices.

IN OTHER NEWS 🗞

🇮🇳 The UK and India have signed a trade deal worth nearly £6 billion. The deal creates over 2,000 UK jobs and cuts tariffs on key goods. British firms will find it cheaper to sell to India, with tariffs on some products dropping from 15% to 3% (on whisky, it’s dropped from 150% to 40%!). Indian companies are also investing into the UK, in areas like AI, aerospace and manufacturing.

💼 Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer just posted record financial results before merging with US firm Kramer Levin. Profit increased by 9.5% from the previous financial year to £487 million, while revenue rose by 4% to £1.3 billion (12 consecutive years of growth). New offices in Luxembourg and Germany helped boost its European reach. CEO Justin D’Agostino called the Kramer Levin merger a key move to expand in the US — something the firm had been aiming for.

⚖️ A long-running legal fight over equal pay could cost UK supermarkets millions. It began with a win against Next in 2024 (we wrote about that), where the tribunal found female shop workers were paid less than warehouse staff. The same law firm, Leigh Day, is also leading claims against Tesco, Asda, Co-op, Morrisons, and Sainsbury’s. These cases move slowly — equal pay litigation often does – but recent failed appeals by Next and Tesco could lead to even more workers joining in.

💳 Klarna just got the green light from UK regulators to offer savings accounts and debit cards. The move means the Swedish fintech can now compete more directly with Monzo and Revolut. It’s a big shift away from its usual buy now, pay later loans — a market that’s become tougher due to stricter rules and more competition. An IPO is still on the cards, but was paused earlier this year because of Trump’s trade tariffs. For now, Klarna’s betting big on becoming more like a full-service bank.

AROUND THE WEB 🌐

🎧 Music: A simple algorithm-free website to discover new music

🎭 Interesting: Nobel Prize winners are 25x more likely to sing, dance or act — and 17x more likely to paint or sculpt

💸 Patriotic: Americans can now PayPal the government to help pay off the $36 trillion national debt

STUFF THAT MIGHT HELP YOU 👌

📹️ Free application help: If you're applying to commercial law firms, check out my YouTube channel for actionable tips and an insight into the lifestyle of a commercial lawyer in London.

How did you find today's newsletter? |